Classical Hollywood Cynicism

The Art and Commerce of Will Connell's "In Pictures"

By Haden Guest

As denizens of today's media-saturated environment we have become inured to the presence of advertising and commodified imagery wherever we turn. It is has thus become all the more important for us to try and understand the history of the "image" as we understand it today. Thankfully, we are witnessing the emergence of important research aimed in precisely this direction. Photo historians such as Michael Dawson and Sally Stein, for example, are turning to early commercial photography as a means to understand the intricacies of photographic-based media and in doing so are bringing to light man figures who have long since disappeared from popular memory. One of the most important of such figures is Will Connell.

During his long career as a Los Angeles based photographer, teacher and columnist, Will Connell (1898-1961) set out to resolve the paradox of commercial photography. It was Connell's adamant belief that commercial photography was not simply compromised art but rather was the only means by which one could achieve a legitimate artistic practice. For Connell legitimacy was possible only through a photography that was both economically viable and effective as an instrument for communication. In his 1949 text, About Photography, Connell justified his career by stating: "I am a photographer because for me photography is the most satisfactory way of talking to people. It's commercial photography because I like to eat."

As one of the driving forces of Connell's work, the notion of communicability called for an image that was legible without being didactic. Like his contemporaries of the Clarence White School, a group of commercially based art photographers, Connell offered a type of abstract formalism, a project of defamiliarizing subjects that closely followed the cues of Soviet montage techniques. Connell's formalism was, however, tempered by a degree of clear emotional investment: humor, sentimentality, and, above all, a type of humanism. Moreover, while Connell had a remarkably pragmatic view of his chosen trade--a clear rejection of the ars gratia artis philosophy held by many of his early contemporaries--this in no way limited his creative spirit. Indeed, in his numerous commercial, industrial, and independent projects (what he called his "personal WPA"} Connell explored a vital and, at times, quite prescient artistic vision.

A self-taught photographer, Connell began his career in the 1920s in Los Angeles, opening a small downtown studio in 1925. In that same year he began working as a photographic illustrator for Collier's and the Saturday Evening Post. Connell soon became an exhibiting member of the Camera Pictorialists whose members included Edward Weston and Louis Fleckenstein. Yet, while he would maintain considerable contact with the Pictorialist circles throughout his early career, Connell soon found himself at odds with the group by his insistence that photography could not be separated from practical life matters and that art photography represented a type of hopeless romanticism. Again from About Photography:

"In my earlier days while playing around in salon activities I stumbled on one of those apparently self-evident truths: that every picture is a sales attempt, whether it be an effort to sell beauty to a gallery-goer, or soup to a potentially well-fed potential customer. Once I got over the shock that it was not art per se, but the way it influenced people that counted, I was willing to re-embrace the hussy photography, live with her and by her, for life."

In 1931 Connell founded the photography department at Art Center College of Design, where he remained an instructor for thirty years until his death. Connell was also the author for fifteen years (1938-53) of U.S. Camera's popular monthly column, "Counsel by Connell," where Connell insured that practical advice on technical questions were always enlivened by his trademark witticisms. As an educator and columnist Connell became a friendly instructor to the nation, setting off the careers of generations of future photographers including Horace Bristol and Wynn Bullock.

Perhaps the most interesting project of Connell's oeuvre is a work from quite early in his professional career, the 1937 photographic essay, In Pictures: A Hollywood Satire. The work is Connell's definitive project, a crystallization of his dominant concerns and signature style that explores the photographic image as a site for both communicability and humor. Here, Connell assembled a series of playfully satirical portraits of the Hollywood studios as highly legible yet sophisticated visual puns. In Pictures thus demonstrates Connell's deep understanding of the plastic potential of the visual image as well as his thorough knowledge of contemporary montage practices being explored in advertising and avant-garde circles. What one critic said of Connell's work in general holds true of In Pictures: it demonstrates that "photography is not simply graphic...it is telegraphic. It talks."

It is especially interesting to consider In Pictures in light of Connell's earlier experience as a cartoonist in San Francisco. In a similar manner as a cartoon strip, In Pictures offers a mixed media of visual image and text, the latter in the form of both direct captions and a larger accompanying text written by a team of screenwriters and authors headed by the renowned scriptwriter Nunnally Johnson. Moreover, the images are meant to be read in a specific sequence and derive additional meanings from their careful ordering.

The book presents a series of forty-eight full-page photographs, each with a separate title and a segment from the Johnson, et al. text "Hollywood Conference." Never in direct correspondence with the Johnson text, the images instead move independently through an improvised lexicon of the Hollywood workforce to describe such positions as, for example, the consecutive series "Director," "Yes-Men," and "Casting." The first of these images shows the director sitting calmly on his canvas throne (wearing what are now known as "mogul glasses") calling a halt to the eager crew that crowds around him, pen, pad, and telephone clutched in their hands. The director holds one hand high in the air, calling everything to a sudden halt with an air of autocratic indifference. He holds a telephone receiver in the other hand--a more important call has come in. Meanwhile, a beam of bright, unnatural light falls diagonally across the image from an unidentified source. While the light reads as a spotlight from a nearby set it also poses ironically as a heavenly light, falling across the director's lap as if to mock the god-like status granted to him. Alternately, the light can be read as evidence that the director does in fact possess the supernatural powers believed of him, with the silent rapt poses of those around him suggesting disciples more than studio gophers.

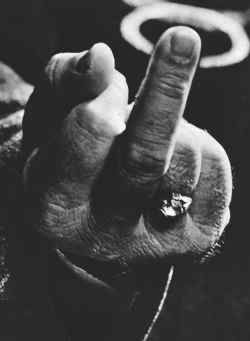

Throughout In Pictures Connell balances a fine line between the grotesque and the playfully humorous. One image titled "Producer" is sheer physical comedy, a distended backside swelling out of both conference chair and plaid suit while a secretary perches a plump behind on the corner of his desk. For this image Connell created an optical illusion by using a miniature chair and extreme wide-angle lens to distort the producer's back to an unnatural girth. While never going so far as the macabre work of Nathanael West or Budd Schulberg, Connell's In Pictures nevertheless bears some resemblance with its evocation of the bizarre and often pungent reality of Hollywood. An image titled "Politics" shows a man's hand in extreme close-up giving "the finger," the titular digit comically ringed by a halo. In another strange coupling of machismo power with religious iconography, the image suggests that in Hollywood crudeness is a cardinal virtue.

Ribald yet never entirely offensive or angry, the photographs of In Pictures read more as one friend poking fun at another, revealing foibles but not taking any real issue with them. As Connell himself stated: "it all comes down to the fact, that once you as photographer have risen above mere mechanical recording your real stock in trade is your taste." Connell did, after all, work as a portrait photographer for Hollywood stars such as Charles Laughton and had many friends in the industry, serving as a lighting consultant for Orson Welles' Citizen Kane in 1940 and a still photographer for David O. Selznick and King Vidor's Duel in the Sun six years later. In Pictures was, moreover, a quite personal project for Connell, aimed more at his circles of LosAngeles friends and acquaintances than at a national audience.

Appropriately, the response from Hollywood was quite amiable. In a 1936 letter Johnson complimented Connell on the "fine bouquet of raspberry which comes out of you and your camera." Another Hollywood acquaintancewrote enthusiastically: "although the story makes us all look pretty sappy, I am delighted because we can see in this Coney Island mirror how distorted we become when we deal with the world's phoneyest [sic] racket." He then added: "this book should be in our public schools."

Copyright © 2000 Capture Productions. All rights reserved.

to find the original of this article click here.

or return to the OnAgenda Will Connell site.